CNNs for Text Classification

How can convolutional filters, which are designed to find spatial patterns, work for pattern-finding in sequences of words? This post will discuss how convolutional neural networks can be used to find general patterns in text and perform text classification. The end of this post specifically addresses training a CNN to classify the sentiment (positive or negative) of movie reviews.

Encoding Words

First, how do we represent text and prepare it as input into a neural network? Let’s focus on the case of classifying movie reviews, though the same techniques can be applied to articles, tweets, search queries, and so on. In the case of movie reviews, we have hundreds of text reviews. Each of which is a few, opinionated sentences long; the length varies.

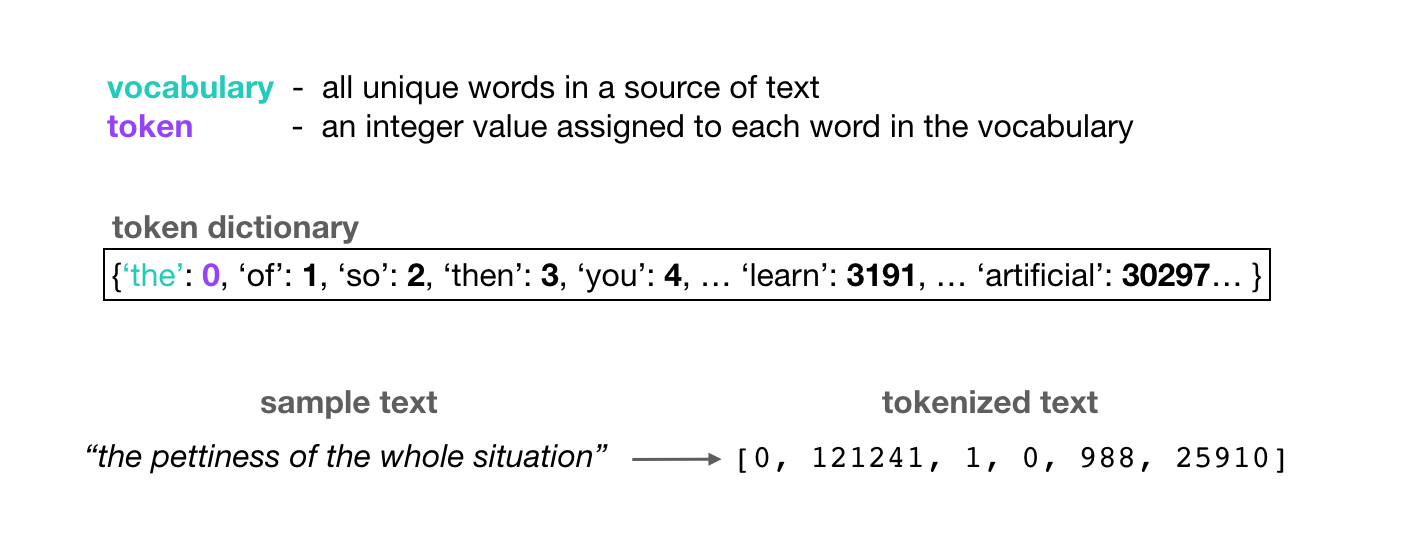

Neural networks can only learn to find patterns in numerical data and so, before we feed a review into a neural network as input, we have to convert each word into a numerical value. This process is often called word encoding or tokenization. A typical encoding process is as follows:

- For all of the text data—in this case, the movie reviews—we record each of the unique words that appear in that dataset and record these as the vocabulary of our model.

- We encode each vocabulary word as a unique integer, called a token. Often, these tokens are assigned based on the frequency of occurrence of a word in the dataset. So, the word that appears most frequently throughout the dataset, will have the associated token: 0. For example, if the most common word was “the,” it would have the associated token value of 0. Then the next most common word will be tokenized as 1, and that process continues.

-

In code, this word-token association is represented in a dictionary that maps each unique word to their token, integer value:

{'the': 0, 'of': 1, 'so': 2, 'then': 3, 'you': 4, … }There are often so many words in a given dataset that these tokens will range from the value 0 to 100,000 or so.

- Finally, after assigning these tokens to individual words, we can then tokenize the entire corpus.

For any document in a dataset, like a single movie review, we treat it as a list of words in a sequence. Then we use the token dictionary to convert this list of words into a list of integer values.

It’s important to note that these token values do not have much conventional meaning. That is, we typically think of the value 1 being close to 2 and farther from 1000. We think of the value 10 as an average of 2 and 18, as another example. However, the word tokenized as 1 is not necessary any more similar to the word tokenized as 2 than it is with a word tokenized as 1000. Typical notions of numeric distance do not tell us anything about the relationships between individual words.

So, we have to take another encoding step; ideally, one that either gets rid of the numerical order of these tokens or one that represents the relationships between words.

One-Hot Vectors

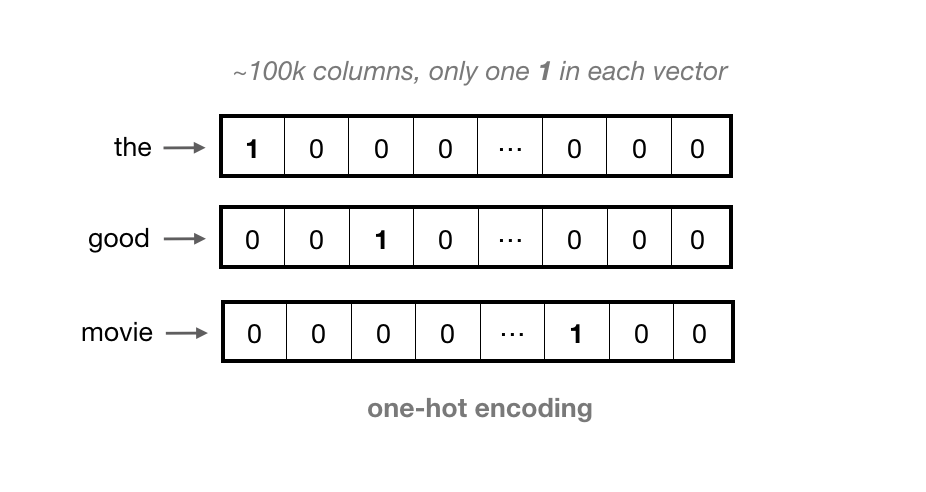

A common encoding step is to one-hot encode each token; representing each word as a vector that has as many values in it as there are words in the vocabulary. That is, each column in a vector represents one possible word in a vocabulary. The vector is filled with 0’s except for the index at that word’s token value, say index 0 for “the”.

For large vocabularies, these vectors can get very long, and they contain all 0’s except for one value. This is considered a very sparse representation.

Word Embeddings (Word2Vec)

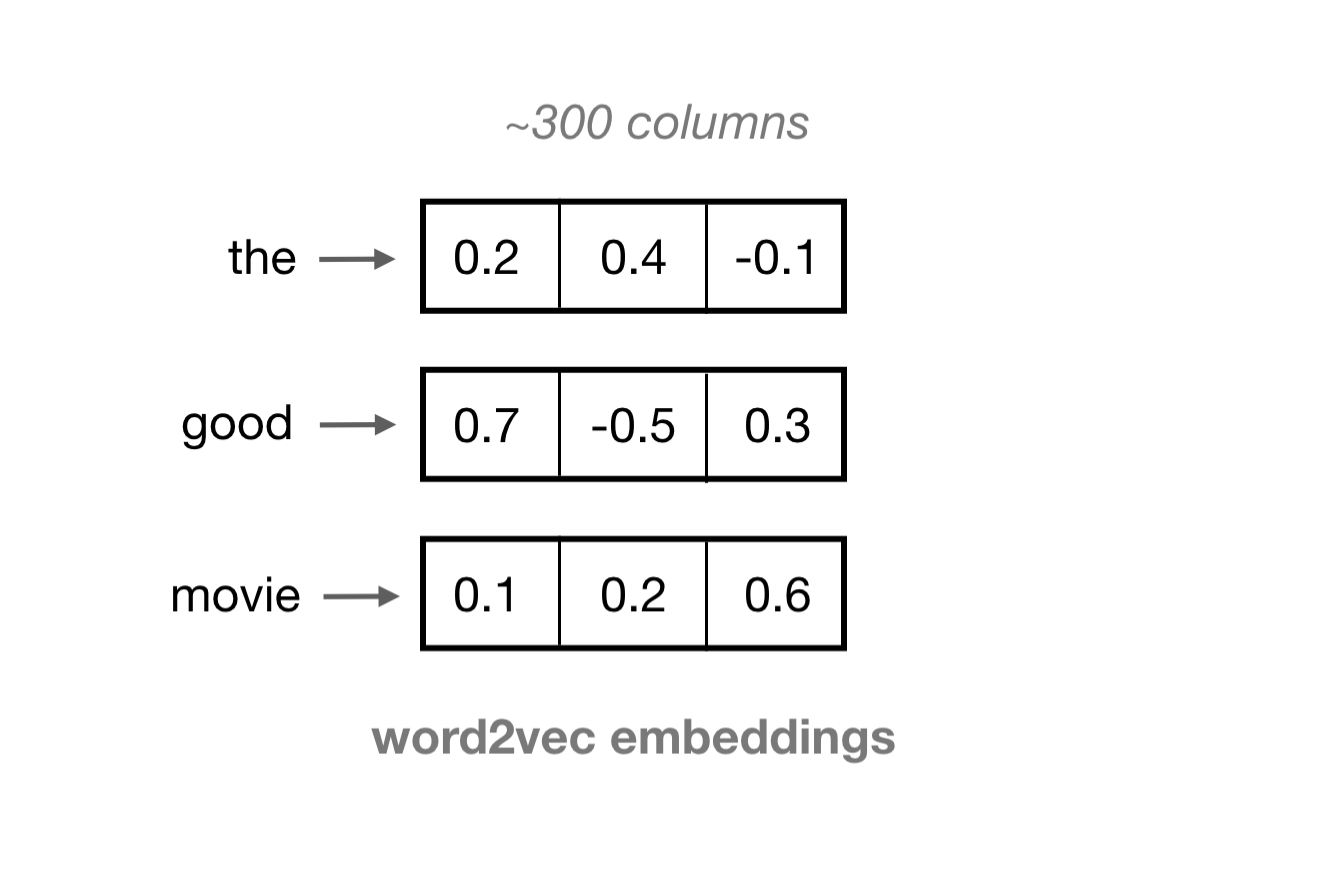

We often want a more dense representation. One such representation is a learned word vector, known as an embedding. Word embeddings are vectors of a specified length, typically on the order of 100, and each vector of 100 or so values, represents one word. The values in each column represent the features of a word, rather than any specific word.

These embeddings are formed in an unsupervised manner by training a single-layer neural network—a Word2Vec model—on an input word and a few surrounding words in a sentence.

Words that show up in similar contexts (and have similar surrounding words), such as “coffee”, “tea”, and “water” will tend to have similar vectors; vectors that point in roughly the same direction. As such, similar words can be found by calculating the cosine similarity between word vectors and you can even add and subtract word vectors to do some interesting word math. If you’d like to learn more about Word2Vec, there are some wonderful resources out there, including this explanatory code example.

These word embeddings have some really nice properties:

- An embedding is a dense, vector representation of a word.

- Words that have similar contexts will tend to have embeddings that point in the same direction.

Similar to how we could encode a single review as a list of tokens, we can now represent a review as a list of word embeddings. These word embeddings can be used as input to a recurrent neural network or a convolutional neural network.

In the code associated with this post, I am going to use a pre-trained Word2Vec model to create word embeddings for a dataset of movie reviews.

Word2Vec and Embedded Bias

One thing to note about Word2Vec, is that, in addition to learning useful similarities and semantic relationships between words, these model also learn to represent problematic relationships between words. For example, a paper on Debiasing Word Embeddings by Bolukbasi et al. (2016), found that the vector-relationship between “man” and “woman” was similar to the relationship between “physician” and “registered nurse” or “shopkeeper” and “housewife” in the trained, Google News Word2Vec model, which I am using in my example implementation.

“In this paper, we quantitatively demonstrate that word-embeddings contain biases in their geometry that reflect gender stereotypes present in broader society. Due to their wide-spread usage as basic features, word embeddings not only reflect such stereotypes but can also amplify them. This poses a significant risk and challenge for machine learning and its applications.”

As such, it is important to note that my example code is using a Word2Vec model that has been shown to encapsulate gender stereotypes. I’d suggest reading this paper to learn about methods for debiasing word embeddings with respect to certain features; this is an ongoing area of research. Next, I will focus on using CNN’s for text classification.

Convolutional Kernels

Convolutional layers are designed to find spatial patterns in an image by sliding a small kernel window over an image. These windows are often small, perhaps 3x3 pixels in size, and each kernel cell has an associated weight. As a kernel slides over an image, pixel-by-pixel, the kernel weights are multiplied by the pixel value in the image underneath, then all the multiplied values are summed up to get an output, filtered pixel value. A detailed description of convolutional filters and convolutional neural networks can be found in a previous post if you’d like to learn more.

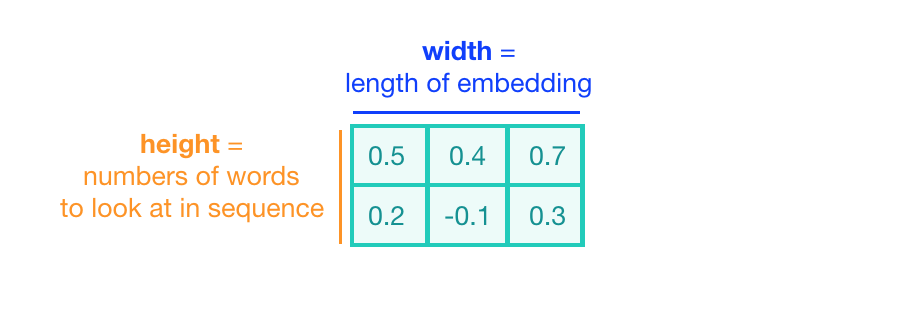

In the case of text classification, a convolutional kernel will still be a sliding window, only its job is to look at embeddings for multiple words, rather than small areas of pixels in an image. The dimensions of the convolutional kernel will also have to change, according to this task. To look at sequences of word embeddings, we want a window to look at multiple word embeddings in a sequence. The kernels will no longer be square, instead, they will be a wide rectangle with dimensions like 3x300 or 5x300 (assuming an embedding length of 300).

- The height of the kernel will be the number of embeddings it will see at once, similar to representing an n-gram in a word model.

- The width of the kernel should span the length of an entire word embedding.

Convolution over Word Sequences

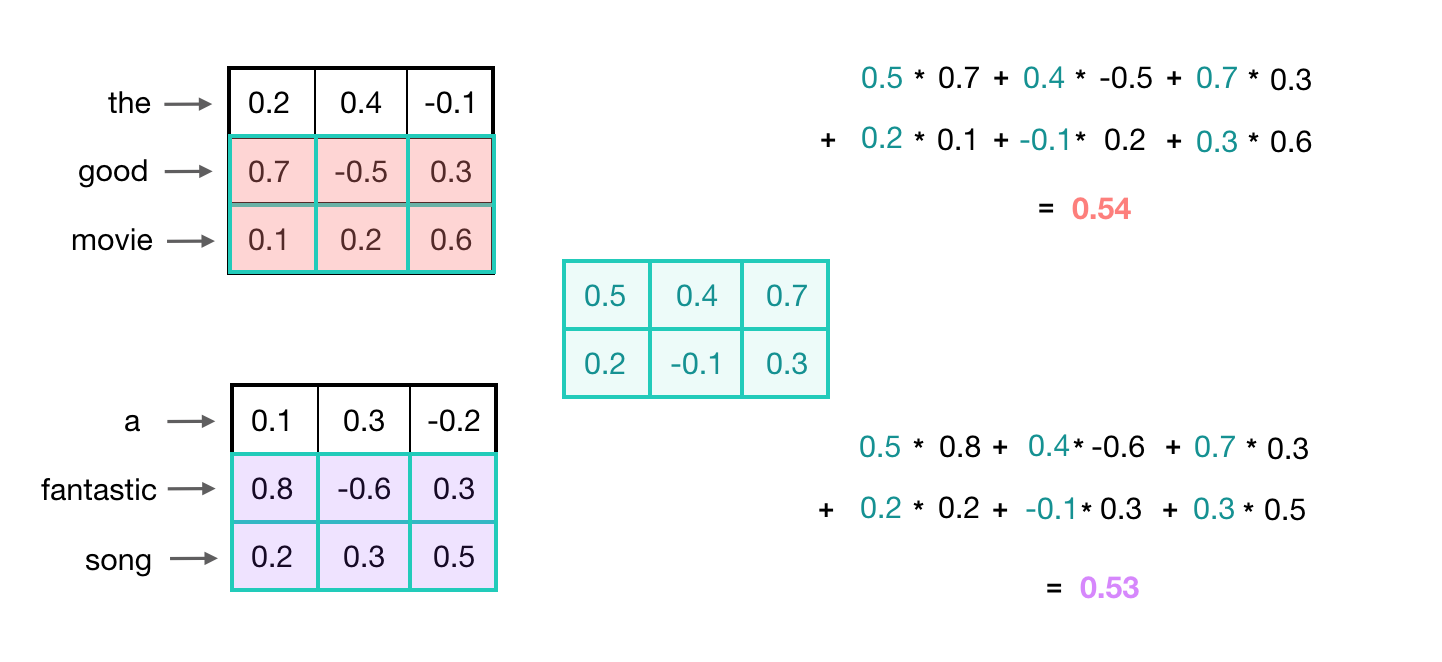

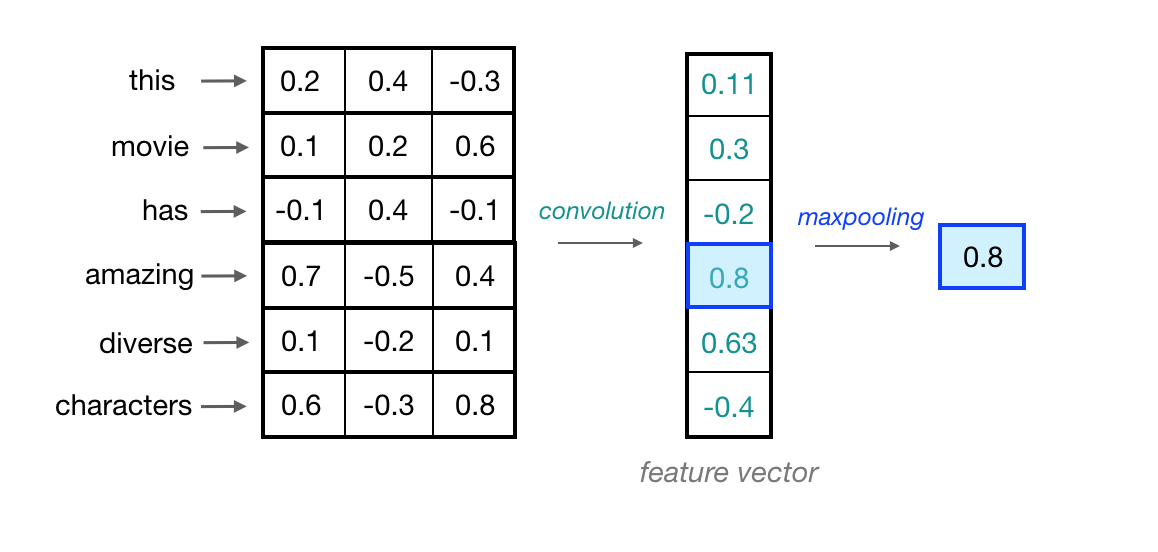

Let’s look at an example of what a pair (a 2-gram) of filtered word embeddings will look like. Below, we have a toy example that shows each word encoded as an embedding with 3 values, usually, this will contain many more values, but this is for ease of visualization.

To look at two words in this example sequence, we can use a 2x3 convolutional kernel. The kernel weights are placed on top of two word embeddings; in this case, the downwards-direction represents time, so, the word “movie” comes right after “good” in this short sequence. The kernel weights and embedding values are multiplied in pairs and then summed to get a single output value of 0.54.

A convolutional neural network will include many of these kernels, and, as the network trains, these kernel weights are learned. Each kernel is designed to look at a word, and surrounding word(s) in a sequential window, and output a value that captures something about that phrase. In this way, the convolution operation can be viewed as window-based feature extraction, where the features are patterns in sequential word groupings that indicate traits like the sentiment of a text, the grammatical function of different words, and so on.

It is also worth noting that the number of input channels for this convolutional layer—a value that is typically 1 for grayscale images or 3 for RGB images—will be 1 in this case, because a single, input text source will be encoded as one list of word embeddings.

Recognizing General Patterns

There is another nice property of this convolutional operation. Recall that similar words will have similar embeddings and a convolution operation is just a linear operation on these vectors. So, when a convolutional kernel is applied to different sets of similar words, it will produce a similar output value!

In the below example, you can see that the convolutional output value for the input 2-grams “good movie” and “fantastic song” are about the same because the word embeddings for those pairs of words are also very similar.

In this example, the convolutional kernel has learned to capture a more general feature; not just a good movie or song, but a positive thing, generally. Recognizing these kinds of high-level features can be especially useful in text classification tasks, which often rely on general groupings. For example, in sentiment analysis, a model would benefit from being able to represent negative, neutral, and positive word groupings. A model could use those general features to classify entire texts.

1D Convolutions

Now, you’ve seen how a convolutional kernel can be applied to a few word embeddings. To process an entire sequence of words, these kernels will slide down a list of word embeddings, in sequence. This is called a 1D convolution because the kernel is moving in only one dimension: time. A single kernel will move one-by-one down a list of input embeddings, looking at the first word embedding (and a small window of next-word embeddings) then the next word embedding, and the next, and so on. The resultant output will be a feature vector that contains about as many values as there were input embeddings, so the input sequence size does matter. I say “about” because sometimes a convolutional kernel will not perfectly overlay on the word embeddings and so some padding may need to be included to account for the height of the kernel. The relationship between padding and kernel size is described in more detail, in a previous post. Below, you can see what the output of a 1D convolution might look like when applied to a short sequence of word embeddings.

Multiple Kernels

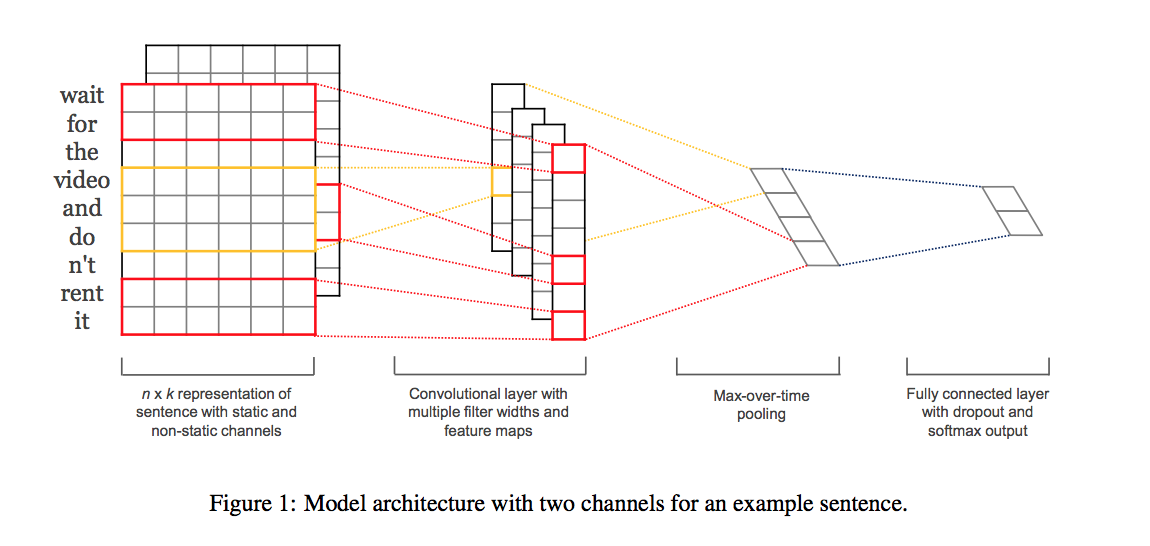

Just like in a typical convolutional neural network, one convolutional kernel is not enough to detect all the different kinds of features that will be useful for a classification task. To set up a network so that it is capable of learning a variety of different relationships between words, you’ll need many filters of different heights. In the paper, Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification (Yoon Kim, 2014) they use 300 kernels total; 100 kernels for each height: 3, 4, and 5. These heights effectively capture patterns in sequential groups of 3, 4, and 5 words. They chose a cutoff of 5 words because words that were farther away than that were generally less relevant or useful with respect to identifying patterns in a phrase. For example, if I say “this apple is red and a banana is yellow” the words that are close together like ‘this’, ‘apple’, and ‘red’ are more related than far apart words like ‘apple’ and ‘yellow’. So, as a short, convolutional kernel slides over word embeddings, one at a time, it is designed to capture local features or features within a nearby window of sequential words. The stacked, output feature vectors that arise from several of these convolutional operations is called a convolutional layer.

Maxpooling over Time

Now, we’ve seen how a convolutional operation produces a feature vector that can represent local features in sequences of word embeddings. One thing to think about is how a feature vector might look when applied to an important phrase in a text source. If we are trying to classify movie reviews, and we see the phrase, “great plot,” it doesn’t matter where this appears in a review; it is a good indicator that this is a positive review, no matter its location in the source text.

In order to indicate the presence of these high-level features, we need a way to identify them in a vector, regardless of the location within the larger input sequence. One way to identify important features, no matter their location in a sequence, is to discard less-relevant, locational information. To do this, we can use a maxpooling operation, which forces the network to retain only the maximum value in a feature vector, which should be the most useful, local feature.

Since this operation is looking at a sequence of local feature values, it is often called maxpooling over time.

The max-values produced by processing each of our convolutional feature vectors will be concatenated and passed to a final, fully-connected layer that can produce as many class scores as a text classification task requires.

CNN for Text Classification: Complete Implementation

We’ve gone over a lot of information and now, I want to summarize by putting all of these concepts together.

- I’ve completed a readable, PyTorch implementation of a sentiment classification CNN that looks at movie reviews as input, and produces a class label (positive or negative) as output, based on the detected sentiment of the input text.

I encourage you to take a look at the complete notebook and look at how movie reviews are processed and what the complete model definition and training steps look like. The notebook includes the following steps:

- Process all the movie reviews and their sentiment labels to remove outliers and encode the labels (positive=1, negative=0)

- Load in a pre-trained Word2Vec model, and use it to tokenize each review

- Pad and standardize each review so that input sequences are of the same length

- Create training, validation, and test sets of data

- Define and train a

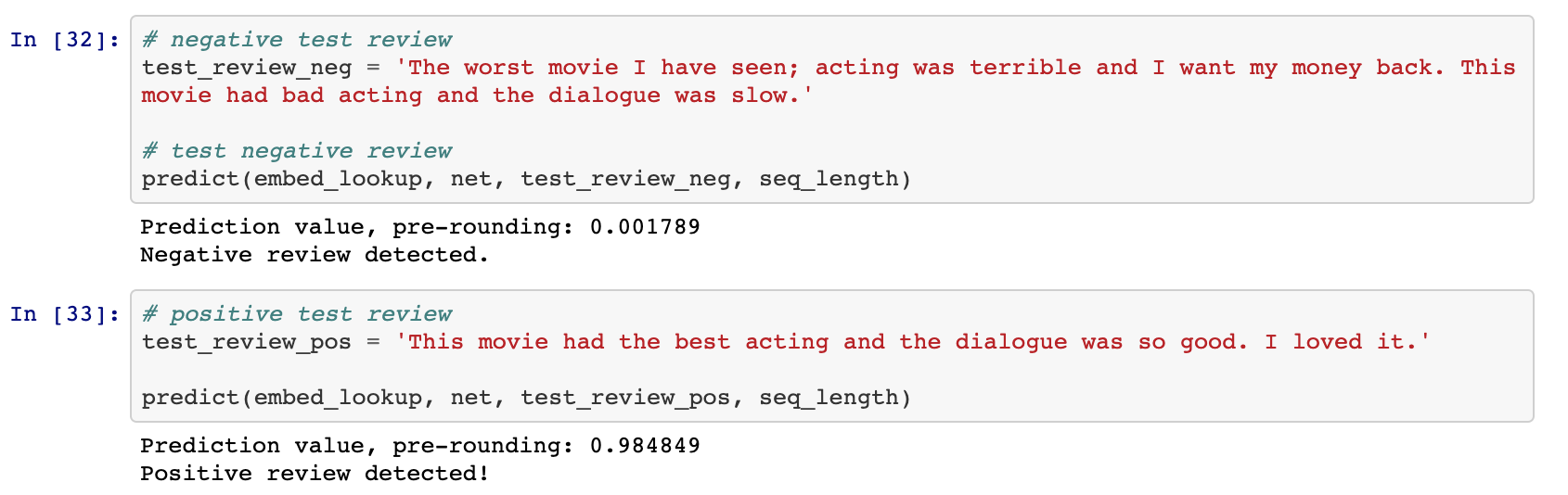

SentimentCNNmodel - Test the model on positive and negative reviews

The example code follows the structure outlined in the paper, Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification by Yoon Kim (2014). It shows how you can utilize convolutional layers to find patterns in sequences of word embeddings and create an effective text classifier using a CNN-based approach.

SentimentCNN

The complete network will see a batch of movie reviews as input. These go through a pre-trained embedding layer, then the sequences of word embeddings go through several convolutional operations, defined in my code as three convolutional layers with kernel heights of 3, 4, and 5. These layers go through a ReLu activation and maxpooling operation. Finally, the max-values from the three different convolutional layers are concatenated and passed to a final, fully-connected, classification layer.

The above image was taken from the original Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification paper (Yoon Kim).

In my implementation, the classification layer is trained to output a single value, between 0 and 1, where close to 0 indicates a negative review and close to 1 indicates a positive review.

After this network trains, you can see how the trained model classifies some sample positive/negative reviews.

Further Learning

As I was writing the text classification code, I found that CNNs are used to analyze sequential data in a number of ways! Here are a couple of papers and applications that I found really interesting:

- CNN for semantic representations and search query retrieval, [paper (Microsoft)].

- CNN for genetic mutation detection, [paper (Nature)].

- CNN for classifying whale sounds via spectogram, [blog post (Google AI)].

I encourage you to read more and try to implement an application that interests you!

If you are interested in my work and thoughts, check out my Twitter or connect with me on LinkedIn.